Municipalities, states and pension managers the nation over have been - in ponzi like fashion - consistently trying to bet on the stock market to help solve their pension liability woes. “Don’t worry, stocks will go up enough!” and “Don’t worry, we can take on debt to solve the problem as an investment carry trade!” have been two popular lines of recent thinking.

For instance, Chicago recently proposed trying to raise billions in debt to help shore up its pension liabilities, ultimately betting that the market would provide returns in excess of what servicing its debt will require. But even in the midst of a bull market over the last decade, investment gains simply haven’t been enough to offset pension liabilities. Maine is a great example. Its public pension fund earned double-digit returns in six of the past nine years but it is still $2.9 billion short of what it needs to afford all future benefits, according to the Wall Street Journal.

This leads retirees, like Daniel Tourtelotte, to ask a simple question: “If the market is doing better, where’s the money?”

This is a microcosm of a problem that is occurring across the nation. The main issue is that the amount owed to retirees is accelerating faster than assets on hand to pay those future obligations. Liabilities of major US pensions are up 64% since 2007, while assets are only up 30%.

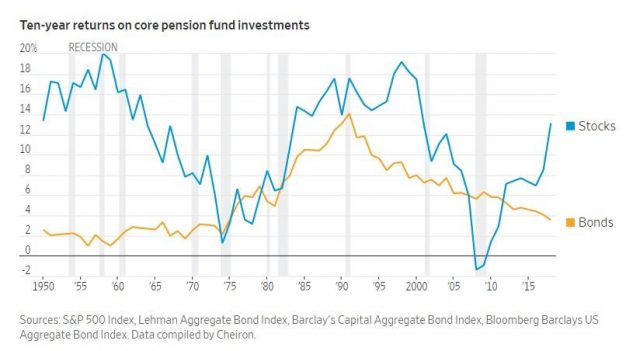

Assets in pensions traditionally rose quicker than liabilities in the five decades starting in the 1950s because the government was expanding and because the number of retirees was smaller. In the 80s and 90s, double digit stock market returns convinced governments that they could afford benefit increases. But shortly thereafter, their assets begin to fall in the aftermath of the dot com bubble, which was shortly followed by the 2008 financial crisis.

As it happens, central banks and the government created new problems in trying to solve the “problem” of a market that badly needed to correct due to years of malinvestments: state and local retirement systems lost 28% into 2008 and 2009. Then, pension funds were forced to chase their bets.

Sandy Matheson, executive director of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System said: “The first thing you have to do is make up what you lost. And it takes years. And then you have to make up what you didn’t earn on what you didn’t have. It’s a pretty steep climb.”

Cities and states then set out to increase their yearly contributions to public pension funds to try and make up for their investment losses. But some simply can’t afford it, as lower tax revenue and increased demand for government services after 2008 resulted in budget crunches. New Jersey, for instance, made less than 15% of its recommended pension payments from 2009 to 2012. Now it has only a little more than 33% of the cash it needs to pay future benefits.

New Jersey State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio said the state is currently: “…on the long road to addressing our unfunded liability after years of neglect.”

Other states, Lake New York, Wisconsin, Tennessee and South Dakota managed to keep assets roughly in line with liabilities through good old-fashioned discipline, cuts, or both. Who would’ve thought cuts, underconsumption and savings discipline would actually have worked?

Many states and cities reduced benefits for new employees after 2008, but these cuts met resistance from unions and constituents, even in indebted states like Illinois. Judges have also offered up resistance. In Illinois, the Supreme Court threw out cuts by the legislature that were expected to save tens of billions of dollars in 2015. Kentucky’s legislature last year declined to approve the governor’s proposed cuts to cost-of-living increases for retired teachers after protests resulted in thousands of people arriving at the state capital and for cancellations of school in numerous district districts.

Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy for the asset-management arm of JPMorgan Chase & Co said: “Some of the states allowed themselves to get so underfunded that the higher returns aren’t helping them enough.”

Maine did wind up cutting cost-of-living increases for both retired and active state workers, who are owed a median pension of $27,000 after 25 or more years service and don’t receive Social Security. However, the cut only reduced the fund’s unfunded liabilities by $1.6 billion - a $2.9 billion liability remains.

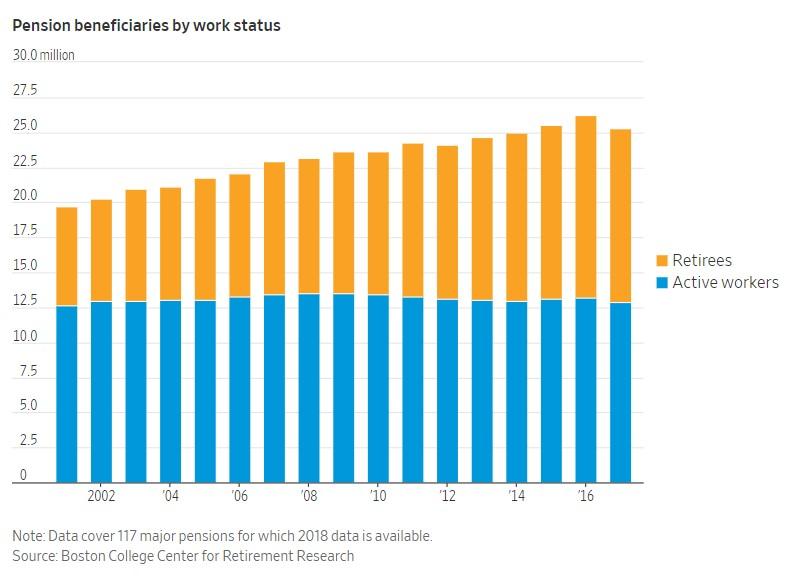

Demographics also played an issue. The number of pensioners went up thanks to longer lifespans and a wave of retirees over the last decade. The number of active workers remained relatively stable.

The state of Maine’s fund serves about the same number of active workers that it did in 2008 - a little bit more than 51,000. However, the number of retirees has jumped 32% to about 45,000. Many other funds in other states are experiencing the same trend. That pattern helps contribute to a gap between pension fund inflows and outflows. This occurs before the funds even earn a dollar on investments. Maine’s pension fund, for instance, paid $982 million in benefits in 2018, which was $394 million more than the contributions it received. This type of deficit makes it very difficult to recover from investment losses.

And so, while some funds have benefited from the ten year long bull market, many are still lowering the predictions of what they can earn in the future. And there doesn’t seem to be any relief on the horizon.

The state of Maine’s pension fund, which in the 1980s assumed a long-term investment return of 10%, now assumes a rate of 6.75%. If that were just 1% higher, the shortfall of $2.9 billion would drop by more than half to $1.1 billion. Still, assuming a “guaranteed” 6.75% return per year, for no reason at all, is certainly optimistic.

The decision to lower the rate was based on discussions with the fund’s actuary and investment consultant as a result of trying to keep costs predictable. “There’s also an element of better safe than sorry,” the system’s executive director said.

Is it any wonder that central banks continue to base monetary policy on the stock market, knowing that if these annual benchmarks aren’t hit, pressure on state and local governments will continue? Yet again, the Fed is trying to solve a problem that it created, by simply creating more problems. And it’s all tied in ponzi like fashion to how the stock market performs.

It makes you wonder who the perpetual line of market dip buyers really are…

via zerohedge

Let’s face it, folks…how many politicians out there have you ever heard calling for the cutting of costs instead of the addition of more cash to solve fiscal problems? So many politicians have no concern for long term consequences as long as their boneheaded lavish spending policies satisfies some political demographic that helps them remain in power. Cutting the costs of government is the most avoided solution by most politicians as exemplified by Obama’s recent management of more than doubling of our national debt……which is historic!

Stop blaming longevity for increased pension liability….it was a known fact decades ago that people were living longer. Stop blaming the stock market for lower returns on investments…the stock market always will have ups and downs. Stop blaming the rising cost of living …the government affects our costs by excessive taxing, regulation, and fiscal incompetance among many more methods. Stop blaming the increase of people who qualify for government pensions….many positions were not necessary to begin with.

The whole pension liability debacle has been caused by those politicians who did not plan for the future or did not care about the consequences of thier lack of remedial action and left the problems to be cleaned up by some other politician (maybe) long after they themselves are out of office. Our Government is it”s own worst enemy!